by Frank Messina

|

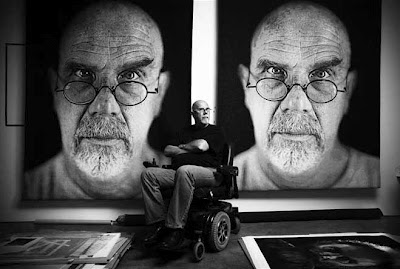

| Chuck Close © Stéphane Israël |

When

I landed the opportunity to interview the most famous artist in

America, I was careful not to fall into the trap of asking the same

questions he's been asked for decades. By doing so would mean

perpetuating the same myth—the same caricature that follows an icon

like a cruel shadow.

So,

instead of asking questions, I chose to listen. Because, when you

listen carefully to seemingly ordinary conversation, extraordinary

things can be heard.

Chuck Close was born July 5, 1940 in Washington State. He

graduated from the

University of Washington School of Art in 1962 and got his Masters of

Fine Arts from Yale University School of Art and Architecture in 1964.

Incredibly prolific and widely acclaimed, his work has been the subject

of over 200 solo exhibitions and 800 group exhibitions. President Obama

recently appointed Close to serve on the President's Committee on the

Arts and the Humanities. With all his accolades, one might expect Close

to be reclusive, reticent and detached. In fact, a very well-noted

journalist friend referred to Close as "most elusive". However, at 71, I

found him accessible, friendly and possessing a healthy and intact

sense of humor. And while the debate in whether or not he likes

journalists is still up for grabs, he admittedly has a deep admiration

for thinkers, poets in particular.

"How are you, Frank?" Close said, in his gravelly baritone voice. "Great," I said. "Just finished grilling a chicken." The simple culinary small-talk triggered a memory that Close eagerly shared. When he was studying at Yale, Robert Rauschenberg came up as a visiting critic to observe the younger artists' work. "He said the place reeks of Matisse. And it probably did," Close said.

"I went to a fresh poultry shop and bought a live chicken—a white chicken, and tied its foot to a pedestal and put a bag over it. And you know, he started to give the chicken a critique, as if it were a real sculpture or something. And the chicken stood up, plucked himself up and took a big shit, a big liquid shit going all across the room, which was hilarious. We thought it was so funny, as if the chicken was giving Bob a review of his criticism."

"How are you, Frank?" Close said, in his gravelly baritone voice. "Great," I said. "Just finished grilling a chicken." The simple culinary small-talk triggered a memory that Close eagerly shared. When he was studying at Yale, Robert Rauschenberg came up as a visiting critic to observe the younger artists' work. "He said the place reeks of Matisse. And it probably did," Close said.

"I went to a fresh poultry shop and bought a live chicken—a white chicken, and tied its foot to a pedestal and put a bag over it. And you know, he started to give the chicken a critique, as if it were a real sculpture or something. And the chicken stood up, plucked himself up and took a big shit, a big liquid shit going all across the room, which was hilarious. We thought it was so funny, as if the chicken was giving Bob a review of his criticism."

|

| © 2012 The Art Story Foundation |

In

1988, Close suffered a collapsed spinal artery which paralyzed him and

confined him to a wheelchair. But as would be expected from an

innovator, Close learned how to cope with his disability. He now paints

using a special device that clips the paint brush to his hand and

forearm.And his studio in New York is equipped with a sophisticated

mechanical easel that moves the canvas up and down, allowing the artist

to remain stationary.

|

| Chuck Close's Self Portrait, © Joe Raedle/Getty Images North America |

Close also refers to his years at Yale as directly challenging everything he'd previously believed about painting the figure. "When [painter] Jack Tworkov took over the art department, he brought up Rauschenberg, [Frank] Stella, and Philip Guston, who I was a student of for the whole time." Tworkov, a legendary figure in the abstract expressionism movement was made Chairman of Yale's art department in 1963. He is best known for re-introducing the figure into abstract expressionist paintings. "There was no way we could've broken yard and shown what we were doing in graduate school as people are doing today. We were reactionary, pretty stuck in the mud," Close said. "And to one degree or another we were trying to find a way out of it. But we just didn't find a way out of it until we left school."

But still, Close credits his teachers for passing down the courage needed for he and his fellow classmates such as Richard Serra, Brice Marden and Nancy Graves to free themselves from their own creative restraints. "It took us all a bunch of years before we figured it out," recounts Close. "So I think being a student, when you're a student, is a very good thing."

|

| Dali Lama, Oil on Canvas, © Chuck Close |

It was only when he moved to New York City in 1968 that he "broke yard" and forced himself free. "Aside from the transitional work I made while in Amherst, I was still making stuff that I didn't think was very interesting. So, what I did was construct a series of limitations with the guarantee that I can no longer make those things and then just see what happens," Close said.

But there was another dilemma: other artists shared the studio with him. Among them, a stubborn silver-haired fellow. "It was occupied with [Willem] de Kooning and people like that," Close said. "They were in the studio with me and I had to get rid of them."

Getting rid of de Kooning—who by that time had a retrospective at New York's Museum of Modern Art, may have seemed like a high hill to climb. But the younger Close stood his ground and before long, de Kooning and the others were gone.

Close describes the time as a cathartic experience: borrowing the tools he "unlearned" from Carone, Rauschenberg, Guston and Vicente. "To just sit in the room finally once it was empty, and figure out what it is that I might want to do—try something. Try something else. Just keep moving," recounts Close. "It was purging."

From 1968 onward, Close produced an enormous catalog of paintings, many of which were large format portraits. His style imparted his paintings with the illusion of a photograph, virtually indiscernible to the naked eye. In 1970 he had his first one-man show at New York's Bykert Gallery and in 1973 his work was exhibited at New York's Museum of Modern Art. And by 1988, at the time of his spinal injury, he was one of the most sought after artists in America, ratcheting impressive sales results both in private sales and public auction.

|

| Chuck Close with Meryl Streep 5/24/12 |

Indeed, Close has amassed many friends in his time. But, he fondly regards poets John Ciardi, John Ashbery, Frank O'Hara and later Allen Ginsberg among his personal mentors. "The great art critics were poets," Close said. "The people we read and listened to were either philosophers or poets."

"And I always preferred the poets."

Chuck Close is represented by:

32 East 57th Street

New York, New York 10022

T (212) 421-3292

New York, New York 10022

T (212) 421-3292

Acknowledgements: Thanks to Bob Holman, Chuck Close, Beth Zopf and the Archives of American Art.

Some of the biographical information on Close was garnered from the following source: www.chuckclose.org

Some of the biographical information on Close was garnered from the following source: www.chuckclose.org

All

photo copyrights revert to the photographer except where noted. All

material copyright protected and may not be copied or

disseminated without the expressed written consent of Chuck Close

Studio, Frank Messina, the Archives of American Art and the

Artist Rights Society.